Alofi is a small island, sister to the island of Futuna, in the Central Pacific. Both are part of the Wallis and Futuna archipelago, today Overseas Territories of France. It is a long trip from Europe.

Alofi is of interest to NAO because Futuna received the visit of a Dutch ship in 1616.

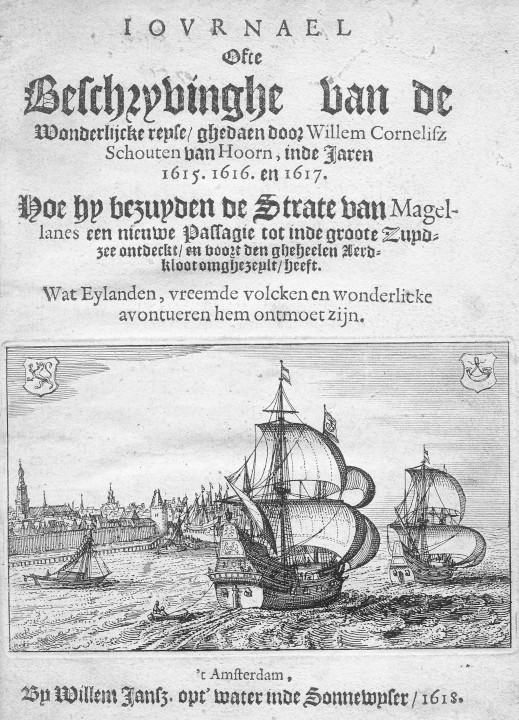

The historical facts are well known [check wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futuna_(Wallis_and_Futuna)]: the ship Eendracht, sailed by Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire, who aimed to follow the steps of Magallanes [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magellan_expedition] ended up encountering in 1616 what they called Hoorn Eylanden, after the city of Hoorn, Schouten’s birthplace. They touched upon Futuna and the chief of Alofi also came to visit them with 300 men (van Spilbergen and J. Le Maire 1621; Engelbrecht and van Herwerden (eds.) 1945). Schouten, the commander of the expedition, later published its diary. His comments made clear that both Futuna and Alofi were highly populated at the time of his visit. Also van Spilbergen and Le Maire wrote that Futuna was populous and Alofi was populated, in line with the archaeological findings. The first census made by the Marist Missionaries in 1841 counted about 840 people for Futuna, and no inhabitants on Alofi, only used for agricultural purposes (Burrows 1936). What happened in these two centuries is the object of NAO’s research on Alofi.

The archipelago had a total lack of exposure to European diseases. Thus, we hypothesized that a likely explanation for the demographic imbalance found by the missionaries was the introduction of diseases in 1616 (Sand 2017; Sand et al 2021).

The project funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and led by María Cruz Berrocal (see below) carried out a field season on Alofi in August 2019. Our challenge on Alofi is not to demonstrate that depopulation happened: anyone who reads the Dutch mention that there were plenty of people on Futuna and Alofi, and reads P. Kirch’s excellent The wet and the dry notices the discrepancies in the numbers. Kirch estimated up to 10,000 people on Futua and up to 3,000 on Alofi in prehistory. Thus, obviously a stark depopulation process took place. The question is, depopulation could have been caused by internal conflicts, war and cannibalism, as the narratives of missionaries seemed to support.

This Eurocentric account would clash directly with the European potential origin for this widespread conflict, namely, the introduction of diseases by the Dutch. Our work on Alofi then was to demonstrate that the depopulation happened in a quick way, compatible with a fast demographic loss caused by disease, and obtain results compatible with this quick demise of the population. This difference is not easy to grasp. Methodologically-wise is not easy, either.

In the first place, we could not trust that specific excavations on particular spots, be it sites or burials, will provide keys to the population over the entire island. Focusing on the mapping and documentation of particular sites was a wrong strategy, so we aimed to gather a holistic view of the archaeological record on the island, through systematic and statistically significant archaeological survey.

This was the main focus of our 2019 season on Alofi, to start approaching its history of settlement. We determined that inland areas were densely inhabited in the past, which is a relevant point to determine the extent of the depopulation suffered by the island. Yet we lacked chronological accuracy, of course a main issue when dealing with surface materials.

The archaeological record provides a baseline to create small-scale hypotheses that can be contrasted. For example, is the depopulation process reflected in a change of settlement patterns? Did people need to defend themselves from a generalized state of conflict and moved towards the interior looking for refuge? Did people permanently live inland, or not? If they did not, was it because it is impossible due to the topography, or because they preferred the coast? Did people live over the entire island until the end of the settlement on Alofi? Is it because it was necessary for survival, or depopulation was so quick that they did not have the time to shift settlements?

But interpreting the surface record is tricky. Both if it shows a change in settlement patterns and if it does not, our interpretation of the record could support a fast demographic collapse. For that reason, Alofi is challenging and fascinating for us. We are still thinking about Alofi, aiming to combine ethnohistorical and ethnographic history, among other lines of evidence, with the archaeological picture.

Gallery

Funding

PI María Cruz Berrocal, September 2018- May 2023 “An Archaeology of first European contact in the Pacific”. Research Grants Programme – Individual Proposal GZ: CR 613/1-1. Projektnummer 395237127. Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

The project was initially for the 2018-2020 period, but it had to be extended to 2023 due to the 2020 pandemic.

Outreach And Publications (Ongoing)

- 2019 María Cruz Berrocal and Jesús García. Seminar Prehistoria en Vivo III, “El abandono de Alofi (Wallis y Futuna, Pacífico Central) tras el contacto europeo, 1616 desde una perspectiva arqueológica”. IIIPC, Universidad de Cantabria, December 16 2019

- 2019 María Cruz Berrocal and Ignasi Grau. Seminar Departamento de Arqueología y Procesos Sociales, “Arqueología después del contacto: reconstruyendo el abandono de Alofi (Wallis y Futuna, Pacífico Central) tras el contacto europeo, 1616”. Instituto de Historia, CSIC, October 30 2019

- An online brief intro to Alofi: https://youtu.be/2RNIi01H9ac?t=1

- Sand, C., Goudiaby, H., García Sánchez, J., Grau Mira, I., Masei, I., Cruz Berrocal, M. 2021 New archaeological data from the abandoned Island of Alofi (Hoorn archipelago, Western Polynesia). Journal of Pacific Archaeology, 12(1), pp. 1–15. Available at: https://pacificarchaeology.org/index.php/journal/article/view/321

Team

Apart from the PI, Christophe Sand (IANCP, New Caledonia), Ignacio Grau Mira (Universidad de Alicante), Jesús García Sánchez (Universität Konstanz) and Hemmamuthé Goudiaby (Universität Konstanz) (both Jesús and Hemmamuthé were hired by the project) were in the field in 2019. Ipasio Masei (Service de la Culture de Wallis et Futuna) kindly joined the team. The Alofi chiefs kindly supported our work and took part in the season: Lafaele Faua (Tui Sa’avaka), Tiele Tufele (Tui Asoa) and Kevin Savea (Vakalasi).

References

Burrows, E. 1936 Ethnology of Futuna. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 138. Bishop Museum, Honolulu

Engelbrecht, W. and van Herwerden, P. (eds.) 1945 De ontdekkingsreis van Jacob le Maire en Willem Cornelisz. Schouten in de jaren 1615-1617. Martinus Nijhoff, ’S-Gravenhage.

Kirch, P. 1994 The wet and the dry: irrigation and agricultural intensification in Polynesia. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Sand, C. 2017 The Abandonment of Alofi Island (Western Polynesia) before Missionary Times. A Consequence of Early European Contact? In María Cruz Berrocal and Cheng-hwa Tsang (eds.) Historical archaeology of early modern colonialism in Asia-Pacific. The Southwest Pacific and Oceanian regions. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 33-56.

Sand, C., Goudiaby, H., García Sánchez, J., Grau Mira, I., Masei, I., Cruz Berrocal, M. 2021 New Archaeological Data from the Abandoned Island of Alofi (Hoorn Archipelago, Western Polynesia). Journal of Paci1c Archaeology– Vol. 12 · No. 2

van Spilbergen, J., Le Maire, J. 1621 Oost ende West-Indische spieghel, waer in beschreven werden de twee laetste navigatien, ghedaen inde jaeren 1614. 1615. 1616. 1617. ende 1618. Janssz ‘t, Amstelredam. urn:nbn:de:0070-disa-136466