NAO [/naʊ/]: ship used by the Iberians for explorations during the 16th and 17th centuries. / Generic name for a ship.

NAO, Networks Across Oceania, points to the ships as vectors that connected both sides of the Pacific, and gave way to the Transpacific world. Thus NAO emphasizes the Pacific a network of places before and after the 16th century.

NAO’s questions can be summarized as which were the impacts on Pacific Island populations and environments, of the recurrent and sometimes intense colonial contacts in the 16th and 17th centuries AD? Most importantly, how can we address this historical problem?

Mainstream historiography, both traditional and critical of Eurocentrism (Cruz Berrocal 2017), conceive the Pacific as an isolated and pristine region until the explorations of Enlightened travelers opened it to global history, mainly through James Cook’s epic and famous voyages (eg. Campbell 1996; Kirch 2000; Boulay 2005; Wolff 2007; Sand 2002). This rhetoric constitutes the historical paradigm that rules Pacific studies (and literature, and popular culture…). This oversizing of Cook’s endeavors has overlooked the existence and extent of earlier encounters between indigenous populations and Europeans (Spanish, Portuguese and much less, Dutch) in the 16th and 17th centuries.

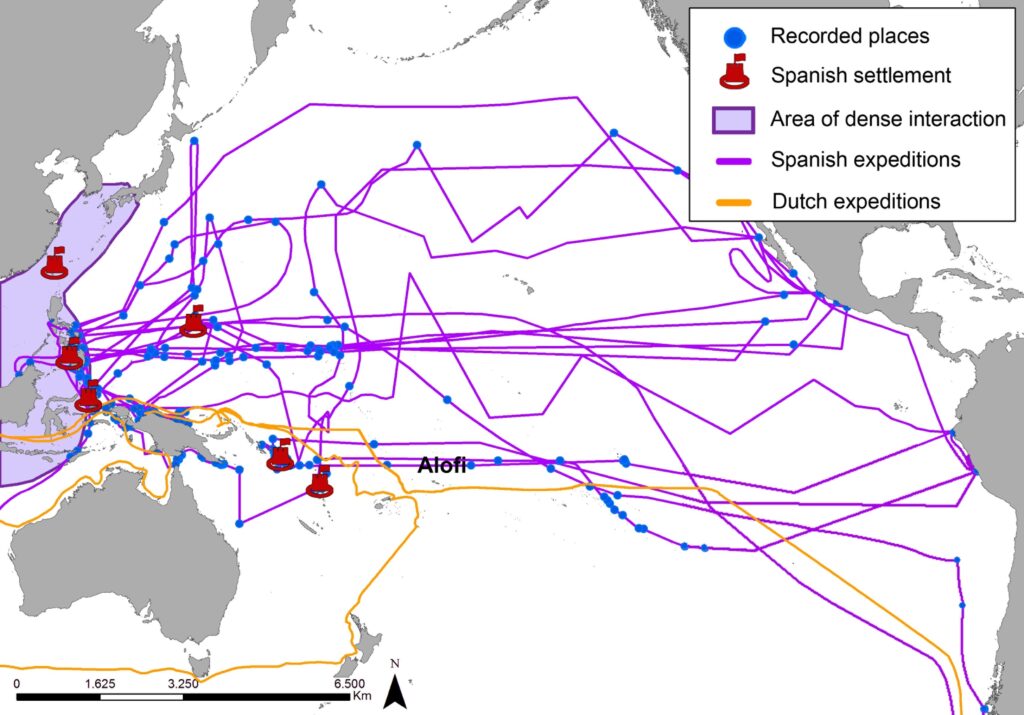

Just an enumeration of the early European expeditions could rise doubts about the post-Cook narrative: 19 Spanish and Dutch expeditions crossed the Pacific between 1521 CE -when the Spanish reached the Mariana Islands and later the Philippines- and 1606 CE -last attempts to colonize Melanesia-. More than 200 places were sighted (implying reciprocal sighting by the locals), contacted or settled in this period. The Manila Galleon was launched in 1565; Manila was founded in 1571; colonies established in Santa Cruz (Nendö) (Solomon Islands) in 1567 and 1595, in Vanuatu in 1606, Taiwan in 1626, and the Marianas in 1668.

These colonial enterprises in the Pacific failed in several occasions, but this does not make them the less colonial or less dramatic for the local populations.

Indeed the main contradiction in the dominant paradigm is this: even short contact episodes in the late 18th century and early 19th century are deemed to have shaped the history of the entire region, causing enormous epidemics. An example is:

“In many island societies intensification was very much an ongoing process when European contact interrupted the pace of history, primarily through the introduction of foreign diseases that undermined economies, decimating their population bases”

(Kirch 2000: 320)

Kirch is referring to the post-Cook contact. However, the consequences that the local peoples suffered through the early colonial episodes have never been systematically investigated. But they cannot have been very different.

Spriggs (1997: 234) hinted the problem this way:

“Could the depopulation of these areas [in the Solomons], extreme even in comparison with other areas of Island Melanesia, have begun with the impact of the Spanish themselves? Diseases common enough among Europeans not to merit comment in the accounts, may have been devastating when introduced to a population with no exposure and, therefore, no resistance to them. The Spanish did not stay long enough in the islands to observe the effects of any such introductions. They note that in all areas the local people appeared healthy and without any evident medical conditions. Later accounts of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries paint a quite different picture in some areas, and the catastrophic effects of the introduction of diseases by passing ships is well documented for that era. (…) Future archaeological projects directed at (…) the areas visited by the Spaniards should allow us to establish whether in fact the decline in population is a phenomenon begun in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries rather than the nineteenth century.”

Archaeological research on Iberian colonialism in the Pacific has developed for several decades now (eg. Allen and Green 1972; Dickinson and Green 1973; Green 1973; Allen 1976; Bedford et al. 2009; Gibbs 2011; McKinnon and Raupp 2011; Blake et al. 2015; Gibbs et al. 2015; Gibbs 2016; Kelloway 2015; Kelloway et al. 2016; Bayman 2017; Flexner and Spriggs 2017; Montón et al. 2020). These are mostly study cases of settlements. NAO has for the first time systematically formulated the problem for the Pacific, compiled scattered evidence, and addressed the implications of such a paradigm change. Among these implications lie a very simple one: the possibility that early Iberian colonialism shaped second-wave European colonialism in late modernity has simply never been explored. However, this novel assumption represents a turn in the understanding of history in the Pacific.

Methodology

The limits of the very conventional archaeology developed so far have been revealed: the excavations have rendered little evidence in the sites where the Europeans settled in Graciosa Bay (Gibbs 2016) and Vanuatu (Bedford et al 2009; Flexner and Spriggs 2017). In Vanuatu, some Spanish material (sherds from one Spanish botija or olive jar), probably from Quirós’ expedition, has been found further north in the Banks Islands (Bedford et al. 2009: 78-84), but nothing on the original colony of Espíritu Santo. The materials in the Banks Islands had probably been incorporated into local trade networks and dispersed from Espíritu Santo, possibly as prestige goods given their exotic origins (Flexner et al. 2016).

Thus, an originally weak material presence is further made invisible by the local social practices. In this way, historical archaeology on this topic, extremely focused on potential recovering of objects from early Iberian colonists, remains incapable of developing an account of historical processes.

Within NAO, through multiple field work seasons on different islands, we have developed particular methodological strategies than can tackle testing of our hypothesis, ie. that early European colonial interaction in different archipelagos was bound to have left a mark on local populations, similarly to what the second-wave European colonialism did.

NAO uses proxies to approximate the impact of early colonialism in the Pacific and its aftermath: plants, animals, and human pathogens were, no doubt, conscious or accidental introductions that travel in the Iberian ships. All of them are likely to have had a significant, if not dramatic, impact on local ecosystems and humans. Thus, together with an exhaustive sampling program targeting newly introduced species in the islands (plants, animals, and even pathogens on human bones), we focus on the effects of the introduction of diseases. For this reason, the first objective when a project is launched is to systematically and thoroughly analyze the settlement patterns on the island, and their shifts through time.

So far, field work in study cases in Fiji, Wallis et Futuna, and the Mariana islands have been implemented by NAO.

Besides these case studies, we have developed research in Heping Dao (Keelung, Taiwan) since 2011, excavating the former Spanish colony of San Salvador de Quelang.

Continue reading

References

Note: references are not intended to be exhaustive.

Allen, J. 1976 New light on the Spanish settlement of the Southeast Solomons: an archaeological approach. In R. Green and M. Cresswell (eds.) Southeast Solomon Islands cultural history. Royal Society of New Zealand Bulletin 11, Wellington: 19-29.

Allen, J., Green, R. 1972 Mendana 1595 and the Fate of the Lost ‘Almiranta’: an archaeological investigation. The Journal of Pacific History 7: 73-91.

Bayman, J. 2017 “Great Powers” in the Pacific Islands: A Calibrated Comparison of Spanish and Anglo-American Colonialism. In M. Cruz Berrocal, Ch. Tsang (eds.) Historical archaeology of the Early Modern Colonialism in Asia-Pacific. The Southwest Pacific and Oceanian regions. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, p. 123-145.

Bedford, S., Dickinson, W., Green, R., Ward, G. 2009 Detritus of Empire: Seventeenth century Spanish pottery from Taumako, Southeast Solomon Islands, and Mota, Northern Vanuatu. Journal of the Polynesian Society 118: 69-90.

Blake, N., Gibbs, M., Roe, D. 2015 Revised Radiocarbon Dates for Mwanihuki, Makira: a ca. 3000 BP aceramic site in the Southeast Solomon Islands. Journal of Pacific Archaeology 6(2): 56-64.

Boulay, R. 2005 Hula hula, pilou pilou, cannibales et vahinés. Paris, Éditions du Chêne.

Campbell, I.C. 1996 [1989] A History of the Pacific Islands. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Dickinson, W., Green, R. 1973 Temper sands in AD 1595: Spanish ware from the Solomon Islands. Journal of the Polynesian Society 82(3): 293-300.

Dixon, B., Jalandoni, A., Craft, C. 2017 The Archaeological Remains of Early Modern Spanish Colonialism on Guam and Their Implications. In M. Cruz Berrocal, Ch. Tsang (eds.) Historical Archaeology of Early Modern Colonialism in Asia-Pacific. The Southwest Pacific and Oceanian Regions. Gainesville, University Press of Florida p. 195-218.

Flexner, J., Spriggs, M. 2017 When early modern colonialism comes late: Historical archaeology in Vanuatu. In M. Cruz Berrocal, Ch. Tsang, Ch. (eds.) Historical archaeology of the Early Modern Colonialism in Asia Pacific. The Southwest Pacific and Oceanian regions. Gainesville, University Press of Florida, p. 57-91.

Gibbs, M. 2011. Beyond the New World – Exploring the Failed Spanish Colonies of the Solomon Islands.» In M.P. Leone, J.M. Schablitsky (eds.) Historical Archaeology and the Importance of Material Things II. Rockville: Society for Historical Archaeology, p. 143-166.

Gibbs, M. 2016 The Failed 16th Century Spanish Colonizing Expeditions to the Solomon Islands, S.W. Pacific. In S. Montón, M. Cruz Berrocal, C. Ruiz (eds.) Archaeologies of Early Modern Spanish Colonialism. Springer, p. 253-279.

Gibbs, M., Duncan, B., Kiko, L. 2015 Spanish Maritime Exploration in the Southwest Pacific. The search for Mendaña’s lost Almiranta, Santa Isabel, 1595. International J. Nautical Archaeology 44(2): 430-438.

Green, R. 1973 The conquest of the Conquistadors. World Archaeology 5(1): 14-31.

Kelloway, S. 2015. On the Edge: a study of Spanish colonisation fleets to the West Pacific and archaeological assemblages from the Solomon Islands. PhD, Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/12872

Kelloway, S., Ferguson, T., Iñañez, J., Vanvalkenburgh, P., Roush, C., Gibbs, M., Glascock, M. 2016 Sherds on the edge: characterization of 16th century colonial Spanish pottery recovered from the Solomon Islands. Archaeometry 58 (4):549-573.

Kirch, P. 2000 On the road of the winds. An archaeological history of the Pacific islands before European contact. University of California Press, Berkeley.

McKinnon, J., Raupp, J. 2011 Potential for Spanish Colonial Archaeology in the Northern Mariana Islands. The MUA Collection, accessed July 25, 2020. http://www.themua.org/collections/items/show/1198

Montón, S., Moragas, N., Bayman, J. 2020 The First Missions in Oceania: Excavations at the Colonial Church and Cemetery of San Dionisio at Humåtak (Guam, Mariana Islands). Journal of Pacific Archaeology 11(2): 62-73.

Landín, A., Barreiro, R., Cominges, A., Génova, J., Guillén, F., Molíns, G., Rodríguez, J.M., Romero, M., Sánchez, L., Vila, C., Viscasillas, J. 1992 Descubrimientos españoles en el Mar del Sur (3 vols). Editorial Naval, Madrid.

Sand, C. 2002. Melanesian tribes vs. Polynesian chiefdoms: recent archaeological assessment of a classic model of sociopolitical types in Oceania. Asian Perspectives, 41(2): 284–96.

Spriggs, M. 1997 The Island Melanesians. Blackwell, Oxford.

Wolff, L. 2007 The Global Perspective of Enlightened Travelers: Philosophic Geography from Siberia to the Pacific Ocean. European Review of History 13: 437-453.

Table

Caption: Pacific islands and island groups sighted or landed on by expeditions since 1521 until the beginning of the 18th century, in chronological order. Mention of particular events or observations is included. The legs of the voyages outside the Pacific, including the Philippines and the Moluccas, are mostly omitted. Elaborated by María Cruz Berrocal and Enrique Capdevila within the NAO project, based mainly on Landín et al. (1992) for the main Spanish voyages. Published in Cruz Berrocal and Sand (2020).

| Date | Expedition | Places | Archipelago | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1519-1522 Cádiz | Fernando de Magallanes | Fakahina | Tuamotu | Approach. Uninhabited. |

| Takaroa | Tuamotu | Pass by. Uninhabited. | ||

| Flint | Tuamotu | Anchor at Flint. Uninhabited. | ||

| Rota | Marianas | Sighting. | ||

| Guam | Marianas | Indigenous welcome. Theft by the natives. Attack and fight. | ||

| Siargao | Philippines | |||

| 1522 Tidore | Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa (Magallanes expedition) | Moluccas | After construction of factory on Tidore, first attempt to cross the Pacific eastwards. Failed. The Portuguese took over all documents and maps. | |

| Doi | Moluccas | Anchor. | ||

| Halmahera | Moluccas | Anchor. | ||

| Sonsorol | Carolines | Sighting. | ||

| Yap, Ggulku, Ulithi, Fais, Sorol | Palau | Sighting. Anchor? | ||

| Agrihan | Marianas | Anchor. «many beast-like people». They take a native onboard. | ||

| Maug, Urracas | Marianas | Survey. 3 Spanish sailors and the Agrihan native desert. | ||

| Ternate | Moluccas | |||

| 1525 | Diego da Rocha | Ngulu | Carolines | Stay in the archipelago until 1526. |

| 1525-1527 A Coruña | García Jofre de Loaísa | Taongi | Marshall | Approach and description. |

| Guam | Marianas | Take onboard one of the deserters who had become the slave of a native. | ||

| Mindanao | Philippines | Deals with the natives. Scape of the forced indigenous from Marianas. | ||

| Talao | Talaud | Refreshments. | ||

| Halmahera | Moluccas | Anchor. | ||

| 1538 Ternate | João Fogaça | Nomwin | Carolines | |

| Papua New Guinea | ||||

| 1527-1529 Zihuatanejo | Álvaro de Saavedra | Namonuito | Carolines | Sighting. |

| Faraulep | Carolines | Landing for four days. Contact with friendly bearded indigenous. | ||

| Antokon | Philippines | Landing on uninhabited island to bury dead, refreshment for 28 days. | ||

| Talikud | Philippines | Anchor. | ||

| Ternate | Moluccas | |||

| 1528 Tidore | Saavedra’s first return | Waigeo | New Guinea | |

| Supiori Biak | Schouten | |||

| Satawal | Carolines | |||

| Marianas | ||||

| Sarangani | Philippines | |||

| 1529 Tidore | Saavedra’s second return | Waigeo | New Guinea | |

| Supiori Biak | Schouten | The natives kill a liberated fellow native forced into the ship the previous year, as he tried to reach land. | ||

| Pulusuk | Carolines | Anchor. | ||

| Puluwat | Carolines | Anchor. Black and bearded natives, attack the ship. | ||

| Nomwin | Carolines | White natives with painted arms and bodies. Friendly attitude. 8 days anchoring, cultural exchange, watering and load of coconuts. | ||

| Marianas | Landing. | |||

| Mindanao | Philippines | Landing. | ||

| Tidore | Moluccas | |||

| 1537 Paita | Hernando de Grijalva | Supiori Biak | New Guinea | |

| Mapia | New Guinea | Landing. Watering | ||

| Waigeo | New Guinea | Landing. Attack by the natives. | ||

| Siriwo river, Warenai river, Sorenwara | New Guinea | |||

| Halmahera | Moluccas | |||

| 1526-1527 Malaca | Jorge de Meneses | Halmahera | Moluccas | |

| Supiori Biak | Schouten | |||

| 1542-1543 Puerto Navidad (México) | Ruy López de Villalobos | Socorro | Revillagigedo | Landing, watering, refreshments. |

| Wotje | Marshall | Landing. | ||

| Kwajalein | Marshall | Sighting. | ||

| Fais | Carolines | Approach. Natives in canoes welcome the ship, salute in Spanish. | ||

| Yap | Carolines | Approach. Natives in canoes welcome the ship. | ||

| Baganga | Philippines | Landing. | ||

| Sarangani | Philippines | Landing. Settlement after expulsion of natives. | ||

| Kawio | Philippines | Hostile natives, fight and annihilation of the population. | ||

| 1545 Samar, Tandaya | Bernardo de la Torre (Villalobos expedition) | Kazan Retto, Chichi-Jima Retto | Japan | Sighting. |

| Farallón de Medinilla, Saipán, Tinián | Marianas | Sighting. | ||

| Samar | Philippines | Discovery of the San Bernardino strait. | ||

| 1545 Tidore (Molucas) | Íñigo Ortiz de Retes (Villalobos expedition) | Talau | Sighting. | |

| Morotai | Moluccas | Pass by. | ||

| Noemfoor | Schouten | Sighting. | ||

| Num | Yapen | Landing. Not welcomed by the natives. | ||

| Koeroedoe | New Guinea | |||

| Mamberamo river | New Guinea | Discovery and possession. Maybe sighted before by Portuguese. | ||

| Pulau Liki, Pulau Nirumoa | Kumamba Islands (New Guinea) | Welcomed by the natives, stay 13 days. | ||

| Masi Masi, Pulau Jamna | Wakdé (New Guinea) | Welcomed by the natives, offered coconuts. | ||

| Podena, Jarsun, Anus | New Guinea | Attacked by natives, said to be black, bare, with arrows without iron, sticks and spears. | ||

| Tendanye, Valif, Kairiru, Unei | Tarawai Islands (New Guinea) | Attacked by the natives. | ||

| Lapar point | (near Aitape) New Guinea | |||

| Vokeo, Koil, Blupblup, Kadovar, Bam | New Guinea | Attacked by the natives. | ||

| Wuwulu | Ninigo Group | |||

| Aua | Ninigo Group | Attacked by the natives. | ||

| Murugue, Besar, Aitape | New Guinea | Landing, Murugue Point and Seleo, Ali, Tumleo islands. Welcomed by natives. | ||

| Awin, Sumasuma | Ninigo Group | White natives. | ||

| 1564-1565 Puerto Navidad (México) | Miguel López de Legazpi | Mejit | Marshall | Landing. Welcomed by the natives who have chicken, potatos, yams. They don’t have weapons, have bone hooks. |

| Ailuk | Marshall | Landing. | ||

| Jemo, Wotho, Ujelang | Marshall | Approach. | ||

| Guam | Marianas | Landing. Indigenous speak in Spanish. Fight but stay for several weeks. | ||

| Samar | Philippines | |||

| 1565 | Esteban Rodríguez (Legazpi expedition) | |||

| 1565 | Pierre Plan (Legazpi expedition) | |||

| 1565 | Jaime Fortún / Diego Martín (Legazpi expedition) | |||

| 1565 | Rodrigo de la Isla Espinosa (Legazpi expedition) | |||

| 1565 Puerto Navidad (México) | Alonso de Arellano (Legazpi expedition) | Likiep | Marshall | Approach. |

| Kwajalein | Marshall | Approach. Sighting of native houses. | ||

| Lib | Marshall | Approach. Black bearded natives in warrior attire come to receive the ship. | ||

| Minto reef | Carolines | |||

| Truk | Carolines | Approach. Friendly natives welcome the ship into the village. 1000 canoes gather and attack. | ||

| Pulap | Carolines | Approach. Natives with long hair sequester 2 Spanish and attack with stones the ship. | ||

| Sorol | Carolines | Attacked by natives. A native boy is sequested. | ||

| Ngulu | Carolines | Pass by. | ||

| Mindanao | Philippines | |||

| Tori Shima | Japan | Pass by. | ||

| Sumisu Jima | Japan | Sighting. | ||

| Cedros | California | |||

| 1565 Cebú | Andrés de Urdaneta (Legazpi expedition) | Parece Vela | Pass by. | |

| Cedros | California | |||

| 1566 Acapulco | Pero Sánchez Pericón | Clipperton | ||

| Erikub | Marshall | Approach. Uninhabited. | ||

| Kwajalein | Marshall | Landing, watering. | ||

| Ujae | Marshall | Landing. Contact with black bearded natives. Bone and shell tools. | ||

| Ujelang | Marshall | 27 mutineers abandoned on land. | ||

| Rota | Marianas | Landing for food and water. Abuse of the natives. | ||

| Samar | Philippines | |||

| 1567-1569 El Callao (Perú) | Álvaro de Mendaña y Sarmiento de Gamboa | Nui | Tuvalu | Approach. 7 canoes approach the ship but no contact is established. |

| Santa Isabel | Solomon Islands | Landing. Friendly relations. Exploration of the area, land and sea. | ||

| Kombuana | Solomon Islands | |||

| Vatilau | Solomon Islands | Landing. Very populated and fertile island. | ||

| Florida, Mbokonimbeti, Soghonara, Mangalonga, Savo | Solomon Islands | |||

| Guadalcanal | Solomon Islands | Settlement. Very populated island, with ginger, porks. | ||

| Malaita | Solomon Islands | Settlement. Friendly relations. | ||

| Ulawa | Solomon Islands | Survey. | ||

| San Jorge, San Nicolás, Arrecifes, Choiseul | Solomon Islands | Survey. | ||

| Olu Malau, Uki Ni Masi | Solomon Islands | Survey. | ||

| San Cristobal | Solomon Islands | Settlement. | ||

| Santa Ana | Solomon Islands | Survey. | ||

| Santa Catalina | Solomon Islands | Survey. | ||

| Maloelap | Marshall | Landing. They find European tools. Uninhabited. | ||

| Wake | Landing. | |||

| 1579 | Francis Drake | Moluccas | ||

| 1596 Manila | Juan Juárez Gallinato | Cambodia | ||

| 1595 Paita | Álvaro de Mendaña, Pedro Fernández de Quirós | Fatu Hiva | Marquesas | Landing. Welcomed by white, bare, long-haired and tattooed natives. Friendly relations, soon abuse of the natives. |

| Mohotani | Marquesas | Pass by. | ||

| Hiva Oa | Marquesas | |||

| Tahuata | Marquesas | Landing. | ||

| Pukapuka, Motu Koe, Motu Kavata | Danger Group | Sighting. | ||

| Niulakita | Tuvalu | Approach. | ||

| Nendö | Santa Cruz | Settlement. First friendly contact, later violent. Disease attacks the Spanish. | ||

| Tinakula, Tomuto Neo, Tomuto Noi, Swallow Group | Santa Cruz | Survey. | ||

| Ponape | Carolines | Approach. Welcomed by natives in canoes. | ||

| Guam | Marianas | Approach. Exchange of iron for food. | ||

| Samar | Philippines | |||

| 1598 Manila | Juan Tello de Aguirre | Siam | ||

| 1598 Manila | Luis Pérez Dasmariñas | Cambodia | ||

| 1603 Manila | Juan Díaz | Cambodia | ||

| 1606 El Callao (Perú) | Pedro Fernández de Quirós | Ducie | Tuamotu | Approach. Apparently uninhabited. |

| Henderson | Tuamotu | Approach. Apparently uninhabited. | ||

| Marutea | Tuamotu | Approach. Apparently uninhabited. | ||

| Maturei-Vavao, Tenarunga, Vahanga, Tenararo | Acteon Group, Tuamotu | Approach. | ||

| Vairaatea | Tuamotu | Approach. | ||

| Hao | Tuamotu | Landing. Friendly relations. Gather coconuts. | ||

| Tauere | Tuamotu | Approach. | ||

| Rekareka | Tuamotu | Approach. | ||

| Raroia | Tuamotu | Approach. | ||

| Caroline | Kiribati | Landing. Gather coconuts and fish. Uninhabited. | ||

| Rakahanga | Manihiki Group | Landing. Friendly natives use outriggers. As time goes by, hostility. No drinking water. | ||

| Taumako | Duff Islands | Landing. Local king Tumai tells them of previous Spanish ships and killing of natives on Nendö. | ||

| Treasurers | Duff Islands | Landing and survey. | ||

| Tikopia | Landing. | |||

| Mera Lava, Merig | Banks Group | Pass by. | ||

| Maewo, Gaua | Vanuatu | Pass by. | ||

| Vanua Lava | Banks Group | Pass by. | ||

| Saddle, Mota | Banks Group | Pass by. | ||

| Espiritu Santo | Vanuatu | Settlement. Contact with natives. They practice agriculture of European and American species. | ||

| Ladhi, Sakau | Vanuatu | |||

| Ureparapara | Banks Group | Sighting. | ||

| Butaritari | Gilbert | Sighting. | ||

| 1606 | Luis Váez de Torres (Quirós expedition) | Malekula | Vanuatu | Sighting. |

| Vanatinai | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Tagula | Bougainville | Anchor. | ||

| Rossel | Bougainville | Sighting. | ||

| Sideia | New Guinea | Landing. Take possession. Fight with the natives. | ||

| Doini | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Domoulin | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Brumer Islands, Baibesiga, Suau, Vehi | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Baxter port | New Guinea | Anchor. | ||

| Bona Bona | New Guinea | Anchor. White natives approach them, no contact. | ||

| Delami | New Guinea | Sighting. | ||

| Imuta, Imbaidora | New Guinea | Approach. Populated, crowded with coconut palms. | ||

| Bonarua, Laluoro, Lopom | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Mailu | New Guinea | Landing. Take possession. Fight with the natives, some of them are sequestered and baptized in Manila. | ||

| Manubada | New Guinea | Anchor for a few days. | ||

| Lagava | New Guinea | Anchor. Native women fishing. | ||

| Parama | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Bristow | New Guinea | Landing. Natives mulattos, darker than the other indigenous seen so far. | ||

| Dungeness | New Guinea | Anchor. Contact with the natives. They eat dog and turtle meat. 3 native women are taken onboard. | ||

| Yam, Gabba, Long, Nagheer, Twin, East Strait | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Endeavour Strait | Australia is sighted. | |||

| Príncipe de Gales | Pass by. | |||

| Australia | Sighted. | |||

| Vals Cape | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Dramai, Aiduma, Baronusu, Sokkos | New Guinea | Landing on Aiduma. Contact with the natives. | ||

| Mauwara, Semisarom | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Lakahia | New Guinea | Landing. Natives live on the trees. Fight. | ||

| Adi | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Serakor | New Guinea | |||

| Panjang, Ekka, Batu Putih | New Guinea | Landing on Panjang, populated with black bearded and long-haired natives. | ||

| Sabuda | New Guinea | Anchor. Remains of a market with Chinese products. | ||

| Schildpad Group | New Guinea | Pass by. | ||

| Jar | Moluccas | Anchor. | ||

| 1614 Strait of Magellan | Joris van Spilbergen | Mariana Islands | ||

| Philippine Islands | ||||

| Ternate | ||||

| 1616 | Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire | Tuamotus | ||

| Tafahi | Tonga | |||

| Niuatoputapu | Tonga | |||

| Niuafo’ou | Tonga | |||

| Futuna | Wallis and Futuna | Stay between April 28 and May 12. | ||

| New Ireland | ||||

| New Guinea | ||||

| Schouten Islands | ||||

| Ternate | ||||

| 1642 Batavia | Abel Tasman | Tasmania | ||

| South Island | New Zealand | Anchor at Wharewharangi Bay. | ||

| North Island | New Zealand | |||

| Tonga | Watering and gathering of food. | |||

| Fiji | Sighting. | |||

| New Guinea | ||||

| 1644 | Abel Tasman | Northern coast | Australia | |

| Torres Strait | ||||

| 1712 | Bernardo de Egoy y Zabala | Palau | ||

| Ulithi | ||||

| Carolines |